Analysis: In a major ‘green paper’, the Government has floated a bold transformation of New Zealand’s transport system in order to reduce emissions and improve public health, but will it follow through? Marc Daalder reports

A new, ambitious package of potential transport policies includes scrapping previously-announced highway projects, slapping distance-based surcharges on car owners and condensing cities into compact, high-density urban areas clustered around rapid public transport arteries.

Even though these policies were the result of more than a year of work by the Ministry of Transport, the Government has already distanced itself from the conclusions that such transformation is needed to meet our emissions targets. Every single one of the report’s 158 pages, including the cover, is firmly stamped with a watermark in all caps: “NOT GOVERNMENT POLICY.” The degree to which the Government will actually consider and implement these recommendations is clearly in doubt.

“While the pathways outlined in Hīkina te Kohupara are not government policy, we want to have a national conversation about the changes we all need to make,” Transport Minister Michael Wood said.

Wood and Climate Change Minister James Shaw said the report would go out for consultation through June 25, ahead of government decisions on the proposals it outlines. Ultimately, final decisions will be revealed in the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan in the second half of the year, which will set out how New Zealand will meet the recommended emissions budgets provided by the Climate Change Commission.

The Ministry of Transport report was largely completed prior to the release of the Commission’s draft recommendations earlier this year, but a fourth modelled trajectory for transport emissions was added to the report in response to that advice. The three original pathways highlighted in the report would not have met the emissions reductions called for by the Commission in the transport sector.

New Zealand’s dirty fleet

While the specifics remain up in the air, the report further showcased agreement among officials and ministers that transport emissions need to fall.

“We’ve already taken steps to reduce emissions but Hīkina te Kohupara shows we have to go much further,” Wood said.

“The pathways laid out in the report show it’s possible to meet our emission reduction targets, but big changes will be needed in the coming decades. There will be some hard choices to make, but it’s obvious we can’t continue with business as usual.”

New Zealand’s transport emissions have nearly doubled since 1990 and are the fastest-growing sector in the economy, from a greenhouse gas perspective. According to the report, they are projected to continue rising under current policy settings through 2024, before stabilising and eventually, slowly, declining. By 2035, when the Climate Change Commission wants to see the transport sector releasing just 8.8 million tonnes of emissions into the atmosphere, forecasts indicate the sector will in fact be responsible for around 15 million tonnes.

The report found that New Zealand’s transport emissions are so high as a result of a heavy reliance on fossil fuels for both personal and freight transport. While just half of freight in Europe moves by road, New Zealand’s freight fleet carries 70 percent of our cargo. Urban sprawl and motorways have furthered our reliance on personal vehicles to get around.

Our vehicles are also dirtier than those used overseas. The average New Zealand light vehicle (a car or SUV) releases the same amount of carbon dioxide in a 10 kilometre trip as the average European van or ute. On a car-to-car basis, New Zealand’s vehicles are 57 percent dirtier and our vans and utes are 38 percent dirtier than Europe’s.

Onus on Government to act

Government has a primary role to play in changing this situation, the report said. At the most basic level, it can do so by demonstrating leadership in decarbonising transport and by collaborating with stakeholders within the sector (local government, industry groups and so on) and those that sit alongside it (the housing sector, or energy, or the tax system).

There is also a place for direct intervention in the sector through investment in new projects, regulations to disincentivise polluting behaviour and incentivise mode-shift or the uptake of low emissions transport and provision of technical and expensive services like modelling transport emissions.

Investment in particular would need to be over and above the National Land Transport Fund (NLTF), which is effectively over-subscribed for the coming decade. About 70 percent of the anticipated revenue in the fund for the next 10 years will be needed to fund maintenance and operation of existing transport infrastructure and ongoing projects will take up most of the remainder in the short-term.

For 2021 through 2024, a November 2020 briefing informed Wood, “Waka Kotahi estimates that around 92 percent of the NLTF will be required to complete already approved/commenced projects, and to maintain system service levels”.

Certainly, the remaining cash in the transport kitty won’t be enough to fund the level of transformation floated in the Ministry of Transport report. That money would have to come directly from the Crown, from local government or from third parties.

Three priorities

The report divides potential interventions into three categories: changing the way we travel, reducing emissions from passenger vehicles and decarbonising freight. While some combination of the three will be needed in any of the pathways modelled by the Ministry of Transport, different trajectories could rely more or less heavily on different options.

The most radical policy proposals, however, are clustered in the first category. This envisions a world where we travel less in general and where, when we do travel, we are far less likely to use a private vehicle than we are today.

That can be achieved through reshaping our cities and towns, the report found.

“Urban form fundamentally affects transport GHG emissions in two connected ways. It affects the distance people need to travel to reach jobs, schools, shops, amenities, and other important destinations. It also influences how they travel, by affecting the range and quality of transport options available, including low carbon modes such as public transport, walking, and cycling,” the Ministry of Transport reported.

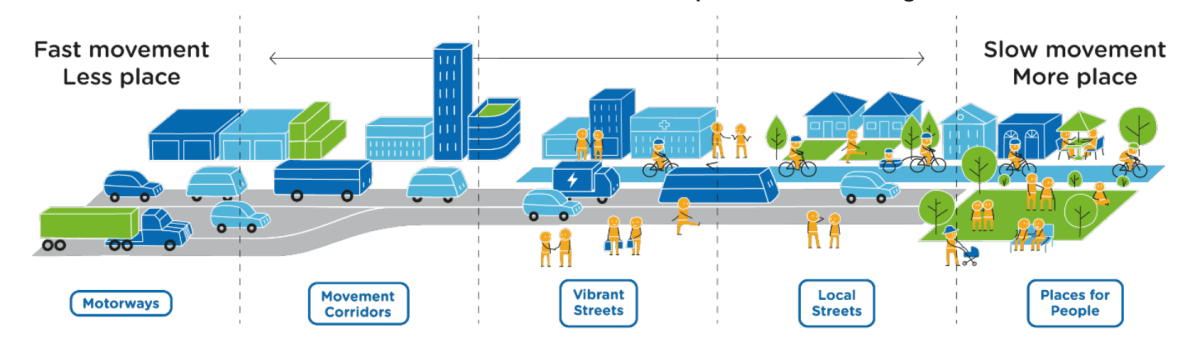

“At the same time, the transport system plays a pivotal role in enabling and shaping urban development. For example, investments to expand urban state highways and major roads (such as road widening and extensions) can encourage urban dispersal/sprawl by making it quicker for people to travel long distances between places by car. This, in turn, leads to more people living in car-oriented suburbs, which causes increasing car use and traffic, emissions, and higher travel times and costs.”

For this reason, the report recommends that central and local government “reconsider planned investments in major urban highway and road expansion projects if they would induce more vehicle travel”. This alone is a significant suggestion. New motorways, like the Mill Road extensions in Auckland challenged at the High Court, have been the bread and butter of Government stimulus programmes for decades, and the recovery from Covid-19 is no different.

The Government’s New Zealand Upgrade Programme, announced just ahead of the pandemic in January 2020, committed $5.3 billion to new roads. The Ministry of Transport report now offers the Government an opportunity to rescind some of those pledges and reorient spending to greener transport initiatives.

Reshaping our cities

There’s plenty of green transport to fund, too. The report recommended investing in public, active and rapid transit. Once this infrastructure is in place, denser urban forms would naturally coalesce around it.

New streets should be designed with public and active transport in mind, the report recommended, as well as ceding more space not to asphalt but to green, public places. Some of these changes can be actioned cheaply, too.

“Street changes to support public transport and active travel could potentially be made swiftly and cost-effectively, as it is possible to reallocate space on existing streets to deliver mode shift without building major new infrastructure,” the report found. This is a two-birds-one-stone approach, as reallocating space would reduce ease of access for cars while increasing ease of access for buses, cyclists and pedestrians.

It isn’t all infrastructure, either. The report found regulatory and taxation measures could be used to reduce private vehicle use.

Proposals under the catch-all term “transport pricing” included congestion charging (a recent government report found “there is a strong case for implementing congestion pricing in Auckland for demand management purposes”), an increased fuel tax alongside the Emissions Trading Scheme, Road User Charges based on the distance a car travels or “smart road pricing”, which would use an electronic system to increase the price of driving when a greener alternative is available nearby.

Improving the fleet

For those scenarios where mode-shift isn’t yet workable, the Ministry of Transport also wants to see a greener, safer vehicle fleet. That could be achieved through incentivising the uptake of electric vehicles. More heavy-handed measures, like a ban on the import of fossil fuel vehicles from 2035 and a ban on the use of fossil fuel vehicles from 2050, were also mooted.

The report also found more work is needed to reduce emissions from the fossil fuel vehicles already in the country.

“Given the slow turnover of vehicle fleets, we need to consider options to decarbonise the existing fleet. This includes removing fossil-fuelled vehicles from the fleet and transitioning to biofuels,” the Ministry of Transport wrote.

Vehicles could be removed from the fleet with a scrappage scheme for old, high-emitting cars. The use of biofuel blends at petrol stations – where a certain percentage of the gasoline is replaced with a more sustainable and (somewhat) lower emissions biofuel – could also reduce emissions across the fleet.

Freight under the microscope

There was less creativity available in the third category of policies – targeting emissions from freight. While medium and heavy trucks make up just 3.8 percent of the vehicle fleet, they’re responsible for nearly a quarter of transport emissions. At this stage, however, there aren’t too many opportunities to mitigate those emissions.

Alternate fuels like biofuels or green hydrogen look good, but they haven’t been proven effective at scale yet. Electric trucks are also close to fruition, but are far from widely available.

The report entertains some level of mode-shift here, too, with road freight being moved to train tracks and coastal shipping. This has its limitations, however.

“The amount of freight that can be shifted to these modes is limited due to Aotearoa’s geographical characteristics, market expectations around timeliness and total costs (including transfer costs), limited access to rail and coastal shipping for rural freight users, infrastructure constraints (e.g. fixed tunnel heights for rail), the characteristics of the cargo, as well as the distance travelled,” the report found.

“Road freight tends to be the cheapest option where distances are short and cargo volumes are low and where geographic constraints prohibit cost effective rail and coastal shipping infrastructure.”

Pathways struggle to hit Commission’s targets

While this inability to entirely eliminate emissions from freight doesn’t necessarily imperil New Zealand’s decarbonisation efforts – after all, we’re aiming for net zero emissions in 2050, allowing for some residual long-lived gas emissions to be offset with tree planting – it does throw up problems for the Ministry of Transport’s report.

That’s because the report isn’t aimed at net zero transport emissions, but at zero full stop.

“Other sectors in Aotearoa may find it harder or take longer to reduce emissions in comparison to transport, and therefore may be prioritised over transport when it comes to carbon offsetting. Given this uncertainty, these pathways explore what could be required to take us as close to zero transport GHG emissions as possible. We acknowledge that absolute zero would be very difficult to achieve by 2050,” the Ministry of Transport writes.

So difficult that none of the four modelled scenarios meet that target. Even the closest still involves emitting a million tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2050.

The bigger problem for the report, however, is its failure to meet the much closer targets set out by the Climate Change Commission. In its draft advice, the Commission writes that transport emissions must fall 47 percent by 2035. In the original three pathways modelled by the Ministry of Transport, the farthest transport emissions fell by 2035 was 44 percent.

In order to meet the Commission’s target, the Ministry of Transport simulated a new, fourth pathway, with more optimistic assumptions about the potential supply constraints on electric vehicles and more ambition about beginning to change urban form and improve vehicle efficiency earlier.

However, this fourth pathway imagines a radically different transport system than that proposed by the Climate Change Commission. In order to reduce emissions sufficiently, the Ministry of Transport sees the light fleet shrinking by 15 percent while the number of public transport buses more than quadruples. Just a quarter of the remaining light passenger fleet is electric.

That’s a far cry from the Climate Change Commission’s scenario, where the total size of the light fleet rises by 19 percent, the total number of buses just doubles and where 42 percent of the light fleet is electric.

Clearly, the Ministry of Transport struggled to reproduce the Climate Change Commission’s pathway with its own modelling. That modelling may have been more limited – it didn’t look at how urban design could affect vehicle usage and emissions, it left out the impact of working from home and excluded the effects of the Government purchasing more electric vehicles.

“Meeting a zero carbon target by 2050 requires a major transformation of the transport system. Currently, our modelling suggests Pathway 1 would come the closest to realistically meeting the level of GHG emissions required. In contrast, Pathway 4 comes closest to the target set down in the Commission’s draft advice, but makes bold assumptions to get there,” the ministry wrote.

“This ambition requires Aotearoa to implement a large number of policies to have a feasible chance of us getting close to it. This will require early and significant effort from all of us.”

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Thank you, your article surprised me, there is such an excellent point of view. Thank you for sharing, I learned a lot. http://solana-preco.cryptostarthome.com

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.

Your point of view caught my eye and was very interesting. Thanks. I have a question for you.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good. https://www.binance.com/join?ref=P9L9FQKY